What if our most fundamental way of perceiving others is an illusion?

Kids are tired of the gendered cage and we can help

Recently, a reader reached out to me about her sometimes gender-nonconforming kid:

My ten-year-old son (born male) identifies as a boy but sometimes likes to wear “girls’ clothes.” I think we should let him do as he likes and be careful not to shame him. My husband, though, kind of freaks out when he sees him, not because he cares that he’s crossing traditional gender lines, but because he worries about how our little guy will be treated in the world. Of course, I’m scared about that too, especially because he’s a really sensitive kid and has the added layer of being a person of color, and I want him to be safe emotionally and physically. I feel like we’re stuck between shaming him ourselves if we stop him or letting him be shamed (or worse) out in the world if we don’t. Help!

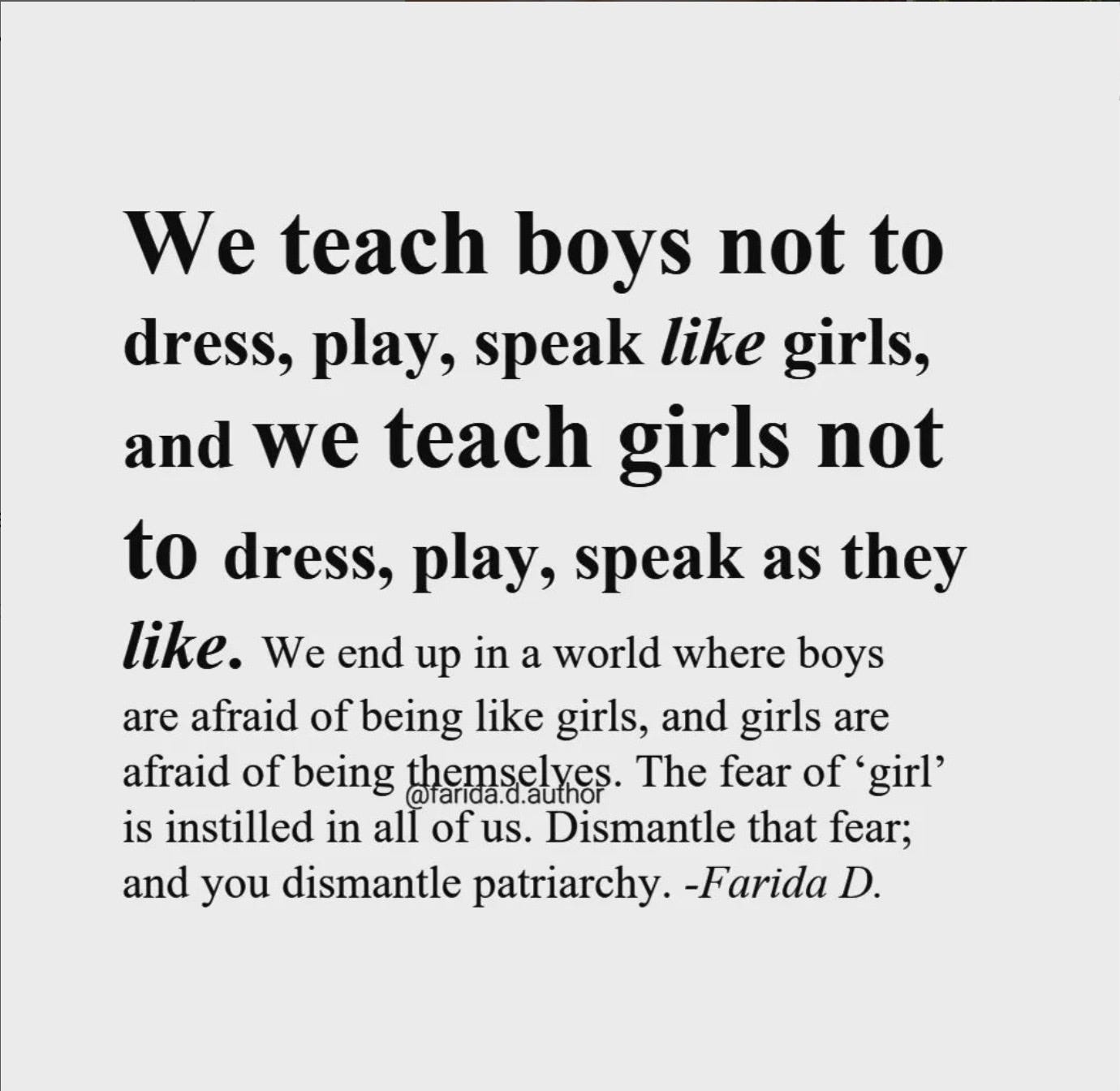

Gawd, parenting is so hard, isn’t it? And when your kids color outside the lines, it’s even harder. The lines of course are bullshit, especially when it comes to gender and race, and are created by a culture hellbent on hierarchy. Why does it catch our attention or matter so much to some people when a boy wears a dress? The answer is because for a boy to become like a girl in any way is to sacrifice status. We wonder who in their right mind would do that? Our male-centric value system tells us feminine things are considered vapid and superficial and masculine interests are respectable. So economic power is valued over intimacy, baseball over fashion, pants over dresses.

Most of you who read my newsletter are well-aware of the limits that come with rigid gender norms. Yet, a binary gender structure is easy. It’s shorthand for what clothing or toys to buy and what to expect. For girls, stereotypically that means being demure, nurturing, agreeable, sexually naive and wearing colorful, adorned clothing. For boys, it means being active, aggressive, in charge, sexually experienced, and wearing muted colors and boring clothing. When someone crosses the divide, it challenges our ingrained, generations-old conviction of well-defined gender roles.

We’ve come to believe these gender roles always existed and so must be biologically driven. But the broader, more creative world of gender isn’t a twenty-first-century creation, though it’s more mainstream than at any other time in history. Many indigenous cultures held more fluid and dynamic understandings of gender, recognizing at least four genders (feminine female, masculine female, feminine male, masculine male) before being subjected to European theories of gender. What if our most fundamental way of perceiving others is an illusion?

Kids of all genders, including those who are cisgender, tell us understanding gender as a spectrum is liberating and truer to their experience.

Kids of all genders, including those who are cisgender, tell us understanding gender as a spectrum is liberating and truer to their experience. Indeed, a majority of the Gen Z set believes there are more than two genders, and one out of eighteen young adults identify as something other than male or female. Even though heterosexuality and a binary gender identity are what we’ve decided is “normal” in the larger population, most kids given the space to explore will fall somewhere along these continuums and not at either end. Yet everything—behavior, clothing, relationships, and identities—is measured against that of the cisgender straight person who embodies one end of the binary; kids who don’t behave in heteronormative ways are often forced to explain themselves.

Despite major backlash in recent years, U.S. culture is increasingly less tolerant of the hierarchies that disadvantage gender-nonconforming people like the reader’s son, and kids are leading the charge. They’re a generation more open to recognizing the complexities of sex, sexuality, and gender. They’re fluent in gender diversity and alternative pronouns. They’re tired of men being valued more than women, heterosexual folks more than LGBTQ+ people, and those who conform to gender stereotypes more than those who don’t. They see more clearly than prior generations that masculinity’s status is maintained by the deprecation of femininity and homosexuality and that girls are sexualized as a means of putting them in their place. They’re in the midst of a revolution, trying to escape the carefully drawn lines that keep boys and girls in their respective lanes. One-quarter of Gen Z kids across the world expect to change their gender identity at least once during their lifetime. Their younger brains do not fight fluidity the way ours do.

While some see the explosion of diverse gender identities and expressions as a trend that will fade, I take its wide embrace by kids today as a sign that our hypergendered world has been a hindrance to youths doing the developmentally important work of figuring who they are. Most will not identify as trans. They’re just tired of the gendered cage.

As I’ve said before, there’s great freedom and relief in not being required to make choices about your identity, your likes and dislikes, and your presentation to the world before you really get to experience who you are. For girls, it’s a respite from the sexualized, commercialized, heteroeroticized femininity that provides little appreciation for other ways to be a girl. For boys, it’s permission to be less inhibited in their bodily and emotional expression.

Embracing gender as a continuum reduces stereotypes, and that’s a good thing for everyone

While we don’t have to contradict kids who insist they aren’t the sex we told them they were, we also don’t need to make a whole lot of meaning out of their proclamations. If we impose our own ideas of gender on our children, whether that means refusing to accept a boy’s love of dresses or rushing to label that child a girl, we risk unwittingly calcifying traditional categories. Embracing gender as a continuum reduces stereotypes, and that’s a good thing for everyone.

So how should this reader and her husband handle their son’s wish to dress like a girl? The fact that she put quotation marks around girls’ clothes (as I did around cross-dressing in the title) says she gets the wackiness of rigid gender norms. I mean, why can’t stores just have a kids’ clothing section where kids can choose what they like and reject what they don’t? Instead, they’re ushered into a particular section and told what they like. I also appreciate her attention to her son’s psychological and physical wellbeing and that while she and her husband could easily have become polarized (as many couples do in similar situations), they seem to be teaming up to figure out how best to parent their child. I’m going to answer her by speaking to all readers because all of us can benefit from the considerations below, whether or not we have a child who is playing with gender norms.

The single most helpful thing any of us can do as caregivers is to examine our own biases so we aren’t parenting from a place of fear. The fear of being hurt in the world is real. The fear it means something is wrong with your child, or you did something to cause this girliness (or whatever the social difference is) is not.

Remember that gender nonconformity and gender identity aren’t the same thing, even if they sometimes overlap. Sure, there’s a slight possibility their son’s wish could be indicative of a transgender identity but a) he’s not saying that and b) even if he were, it’s crucial to remain open and curious with kids. The wish to be a different sex can dissipate as kids age, or come instead to signify being attracted to someone of the same sex, or suggest they just don’t fit traditional stereotypes. Or their wish may be indicative of a transgender identity. We can affirm without pushing a particular outcome. The goal is to not foreclose on their identity.

Come clean with your kid. Explain stereotypes. Tell them the world will try to put them in boxes and if they don’t fit neatly, they might be rejected or mocked. It’s not fair but it’s a problem with the culture, not with them. If they ask why, tell them people like to know what to expect, that it can threaten their sense of right and wrong, or that they may even unconsciously feel envy because they don’t feel they’re allowed to dress like that. Always balance the darkness with hope: “The good news is, the world is changing. People are fighting for the right for boys and girls to express themselves in whatever ways they like. In some places you have to be more careful than others, but at home you’re always free to be you.”

It’s incredibly difficult to undo shame. Parents can reduce that risk by being conscious not to reinforce the gender binary in the hundreds of small ways that we all do. For example, we divide kids into girl and boy groups. Instead, we (and their teachers) can use first initials, birth dates, dogs and cats, winter and summer. We can refer to them as a helpful kid rather than a helpful girl. We can put up signs that recognize gender diversity like “All genders welcome” and hire a male housecleaner, a female handywoman, or a nonbinary tutor to reject stereotypes and normalize differences. Getting to know other families with gender-nonconforming kids will serve to normalize gender expansiveness and teach kids that different, in all its iterations, is good, beautiful, and often brave.

In the Western world, we over-assign gendered meanings to anatomical sex, and we’ve relied on a long history of stereotypes to determine what’s right and wrong for each sex. But gender norms have always been dependent on place and time; little more than a social construct shaped by years of history and evolving fashions. Dresses, heels, wigs, makeup, and the color pink, for example, were all once worn by boys or men. It’s absurd how adamantly we argue now these things are for girls only.

Jo-Ann,

Thank you for this insightful article. I admit I probably most resonate with the father in this situation. I come from a past place of homophobia. I’m happy to report that that place is changing, even in the people that (accidentally?) raised me to be homophobic. (Or, all the “phobics.”) I am learning how to be affirming, but sometimes the old ways, and I guess I should include patriarchy, are really hard to recognize even myself. This article helped quite a bit. I am hopeful it will help me move one step further to a better place of acceptance and understanding, affirmation and love.

Such a balanced, informative and helpful answer for all of us wondering how to help kuds feel safe when they're outside the "box" society tries to keep them in (and people are understandably scared tio challenge). This gives us courage to challenge, with love and understanding!

Monica